Left to suffer: A woman’s unrelenting battle with cancer, stigma

Her battle began in 2015 when she was diagnosed with Stage 3B breast cancer. At the time, she was a working mother and wife, trying to balance her career while raising a young child. The diagnosis changed everything.

“Why would I fake cancer?” These are the haunting words Sarah Wangui, 42, repeats to herself daily. From her hospital bed at Kenyatta National Hospital, her voice is barely louder than a whisper, but the pain and disbelief behind the question cut deep.

After nearly a decade of fighting different forms of cancer, Wangui not only battles the disease but also the stigma, judgment and emotional isolation that too often accompany it.

More To Read

- Court freezes ex-KNH CEO Evanson Kamuri's assets worth Sh229 million

- KNH conducts complex facial reconstruction surgery on young boy injured in Isiolo-Meru bandit attack

- Senators sound alarm over overcrowding, security lapses at KNH

- New study links oral hygiene to pancreatic cancer risk

- WHO warns global fight against non-communicable diseases is stalling

- How cancer misinformation exploits the way we think

Her battle began in 2015 when she was diagnosed with Stage 3B breast cancer. At the time, she was a working mother and wife, trying to balance her career while raising a young child. The diagnosis changed everything.

“It hit us like a storm, suddenly; life stopped. There was fear and confusion,” she says.

The physical toll of cancer was just the beginning. As treatment progressed and the burden on the household grew heavier, her marriage fell apart. Her husband left, unwilling to cope with the demands of her illness.

“He walked away. Just like that. I was left with a child to raise and a disease to fight.”

Still, Wangui soldiered on. She underwent a mastectomy and six gruelling cycles of chemotherapy. With the support of her parents, siblings and close friends, she endured the pain, fatigue and emotional strain.

By the end of 2016, her doctors declared her cancer-free. “I went to church, told my family and friends, and we celebrated. It felt like we could breathe again.”

But cancer can be unpredictable and cruel. A few months later, during a routine follow-up visit, tests revealed the cancer had returned, more aggressive than before.

Wangui was devastated. “I couldn’t even cry. I just sat there, numb. My body had just started to recover. My hair was growing back. My life was beginning to feel normal again.”

With her strength fading and the cost of treatment rising, she turned once again to those around her. While some friends and family offered support, others reacted with scepticism and even cruelty.

“I heard people say I was faking cancer for sympathy or financial help. That I just wanted attention. It’s painful. No one wishes this on themselves,” she says.

After another mastectomy and further treatments, funded by donations and NHIF, Wangui once again hoped she could return to a normal life. But in late 2024, her health began to deteriorate rapidly.

“I started having trouble breathing. I thought it was just fatigue, or maybe pneumonia,” she says.

She was diagnosed with lung cancer. Doctors drained nearly 0.7 litres of fluid from her lungs. The diagnosis felt like betrayal.

“How do you explain to people that it’s not your breast anymore; it’s now your lungs? How do you keep asking for help when people are already tired?”

Financial burden

Wangui’s case highlights the gaps in Kenya’s public health system, particularly when it comes to chronic illnesses like cancer. The new Social Health Authority (SHA) provides limited coverage. According to Wangui, it only covers three chemotherapy sessions. After that, patients are left to fend for themselves.

“I used up my SHA limit by February,” she says. “I’ve not had chemotherapy since then. Each session now costs more than Sh150,000, and I have nothing left.”

Previously, during her breast cancer treatment, she paid about Sh10,500 every three weeks. But her current condition requires more advanced and expensive therapies, which she will need for the next few years.

Her voice breaks as she adds, “I don’t work. I depend on well-wishers. And now I have to wait for the new fiscal year for the government to allocate more funds.”

Now admitted to Kenyatta Hospital, Wangui is on oxygen support, growing weaker with each passing day. But even as her body fails her, her spirit fights on. One of the few constants in her life has been the support group Kilele Health, which provides counselling, encouragement and a sense of belonging.

“They remind me I’m not alone. When everyone else walks away, they’re still there.”

Despite everything, Wangui’s message to the world is not one of anger, but of hope.

“To my friends, to my family: please don’t give up on us. No one chooses this life. No one wants to be sick. We just want to live.”

Wangui is just one of thousands of Kenyans facing a similar struggle. Late diagnoses, high treatment costs, limited government cover and societal stigma combine to create a perfect storm for cancer patients.

“People with cancer can't work. Their families get overwhelmed. We need a system that doesn’t abandon us halfway,” she says.

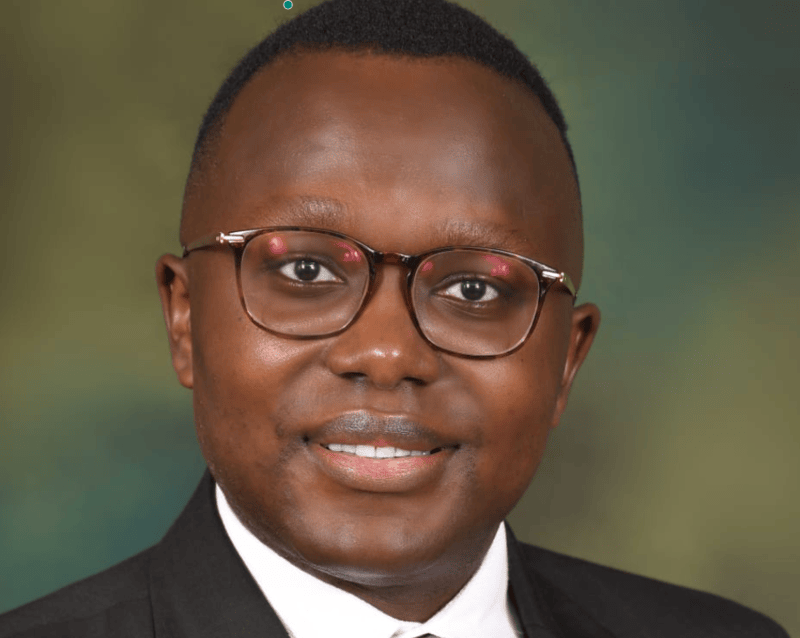

Dr Andrew Odhiambo, a medical oncologist at Prime CancerCare Clinic. (Handout)

Dr Andrew Odhiambo, a medical oncologist at Prime CancerCare Clinic. (Handout)

Dr Andrew Odhiambo, a medical oncologist at Prime CancerCare Clinic, notes that cancer recurrence can be unpredictable, especially when dealing with aggressive disease biology. Certain factors are associated with a higher risk of recurrence, including late-stage diagnosis, particularly stage 3 disease, significant lymph node involvement, and aggressive tumour subtypes such as HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer.

Recurrence is also more commonly observed in younger patients and those of African descent, likely due to genetic and biological factors influencing disease behaviour.

“A crucial aspect in reducing recurrence risk is strict adherence to treatment protocols. Patients who fail to complete chemotherapy, miss radiotherapy appointments, or discontinue any part of their prescribed treatment regimen face a substantially increased likelihood of the cancer returning,” he says.

In contrast, early-stage detection and timely initiation of treatment are strong protective factors, significantly lowering the chances of recurrence.

Lifestyle choices

Lifestyle choices following treatment also play a role in long-term outcomes. Dr Odhiambo advises patients to maintain healthy dietary habits, prioritise immune-boosting foods, sustain a healthy weight, and avoid weight gain after completing chemotherapy. These practices can improve overall prognosis and support the body's ability to recover and remain in remission.

When it comes to cancer recurrence, Dr Odhiambo notes that it is among the most difficult conversations a clinician must have. It must be approached with a high level of empathy and professionalism. The conversation should begin calmly, following established protocols for breaking bad news.

"Offering a 'warning shot'—a gentle statement that prepares the patient emotionally—is important. Listening carefully to the patient’s emotions and reactions, maintaining a compassionate tone, and allowing space for grief or shock are all vital components of this dialogue," he says.

Top Stories Today